You have no items in your cart.

Originally written by Raymond Foye for Brooklyn Rail

For almost sixty years Jordan Belson lived in the same charming corner of San Francisco, the bohemian enclave known as North Beach, named after the region of Italy from where the locals emigrated—the Gulf of Trieste. Rents were cheap and neighbors tolerant. From the mid-1950s, until his death in 2011 at the age of eighty-five, Belson occupied a three-room flat on Montgomery and Vallejo Streets, a dark apartment of exquisite austerity, which I always imagined was inspired by a favorite book of his, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows. The rooms contained beautiful woodwork, rice paper lamps, tatami mats with cushions on the floor, and low shelves with arrangements of Ikebana, fruits, and raku ceramics made by his friend James Whitney. A few choice examples of Belson’s art were discreetly displayed. Belson had blocked up most all the windows, but preserved two sweeping views of the San Francisco Bay and the Oakland Bay bridge, and beyond that the rolling hills of Berkeley and the East Bay. This panorama was a constant drama of fog, clouds, and celestial sun- and moonlight. The artist always said this view was a major influence on his work.

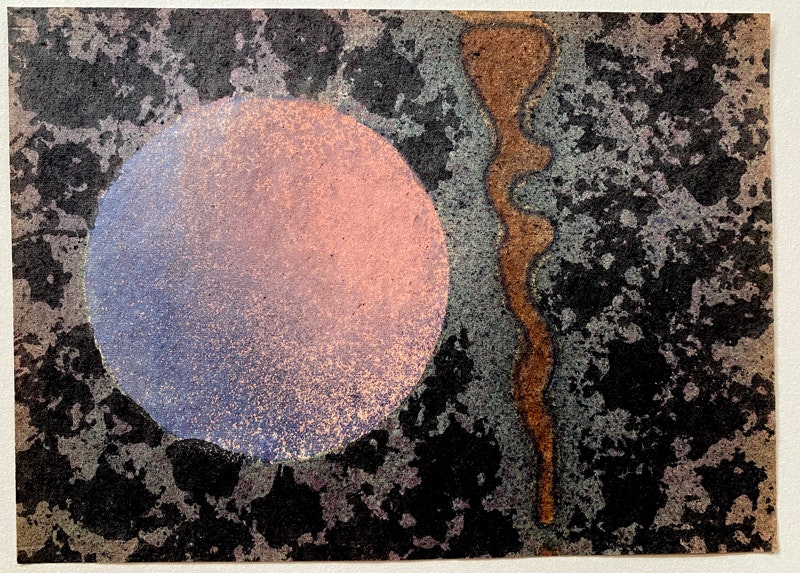

I begin with a description of this apartment, Belson’s home-studio of over five decades, because it always seemed to me to be the perfect emblem of his life pursuit. I often thought of that space almost as a living being. Ingeniously economical, the apartment contained a workspace for making his paintings and pastels—the room with the view. Another room where he made his films housed the “optical bench,” an ingenious configuration of lamps, lenses, colored gels, and rotators and oscillators. The camera was above, attached to an adjustable mount (a former x-ray stand). Belson carefully guarded his simple means of production, wishing to keep people focused on the films themselves. “It’s almost all smoke and mirrors, literally,” he once said to me.

Next to the optical bench was a screening area with cushions on the floor and a 16mm Bell & Howell projector. From lumber and plexiglass Belson constructed a projection booth, to minimize sound. There were two TEAC reel to reel tape recorders with which he made his soundtracks, tape compositions, and recorded hisautoharp music. He also taped off the radio extensively, mostly jazz and classical, editing down favorite compositions to mixtapes.

I visited this apartment many times, but only much later did I learn that Belson had hired his friend Albert Saijo to do the carpentry. Saijo was a Japanese-American poet, author of Trip Trap, a book of haiku written with Jack Kerouac and Lew Welch on a 1959 cross country road trip. Encouraged by Gary Snyder, who suggested the hippies might need a survival guide to the backwoods, Saijo wrote one of the pioneering works of eco-literature, The Backpacker (1972). Along with Ruth Asawa and Arthur Okamura, Saijo was instrumental in introducing Japanese aesthetics to post-war art in the Bay Area. All three artists spent their formative years in Japanese American internment camps during World War II. Poet Philip Whalen recalled that Saijo taught many of the poets how to sit zazen, being the only one who had formal training.

* * *

This was a “synthesis moment,” and one more reason why Belson remains for me a significant figure today. As people are forced or choose to move outside of traditional artistic and urban centers, seeking a more affordable (and pleasurable) life in out-of-the way places, the question of community is ever more critical: How do you sustain an art when almost no one is looking? Belson is a good example of an artist who managed to have a rich and productive life making great art—outside of the art world. His is much more like a poet’s career in its modesty and diligence, and lack of remuneration.

So much attention in the art world is placed on success and celebrity these days, students are seldom ever prepared for the far more likely opposite result. One can take an education in the arts to many other fields and still enjoy the benefits, and many do, but lack of commercial success should not be a reason to abandon a calling. In renouncing the artworld (or was it the art world renouncing him?) Belson proposed an example of another way to function in society as an artist. The larger question is, can there be art without an art world, and how might that exist?

What made Belson’s space so different from other artist’s studios I’ve known is the human scale and domesticity, which made for intimately concentrated paintings. Qualities we associate with the domestic sphere likewise come into play: orderliness, patience, preparedness, modesty, all were essential aspects of his aesthetic. The windows overlooking the bay (actually narrow double glass doors opening on a small balcony) always reminded me of Matisse’s depictions of his hotel rooms in Nice. T. J. Clark has coined the phrase “room space” to describe this felt dimension, the final development of nineteenth century pictorial space, ultimately shattered by cubism and the world wars. “Space is not distance… not a journey to a horizon: it is here where we are, an immense proximity, a total intuition of ‘place’ and ‘extent’,” Clark writes.2

* * *

Allen Ginsberg once said that culture was only ever the same six people, i.e., it only takes half a dozen people to create a social group with enough ingredients to produce the cross-pollination necessary for a new imagining of reality. One gets a sense of this reading Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters (Penguin Books, 2010) where figures like Belson, Philip Lamantia, and Gerd Stern move in and out of the scene, sharing news, ideas, friends, lifestyles, and other connections (including jazz and drugs). Belson’s flat was one block north of the apartment where Allen Ginsberg wrote Howl, and in fact it was Belson who gave Ginsberg the peyote that inspired that poem.3 In 1954 Belson and Ginsberg discussed making a film of William Burroughs’s then-unpublished Naked Lunch, and/or Kerouac’s Doctor Sax, or perhaps another film sympathetic to the Beat sensibility. Unfortunately, this was a project that would have to wait until January 1959 when Al Leslie and Robert Frank made their film Pull My Daisy.4

Referring to Belson as a “Beat” artist is not to categorically define him as such, but only to point out some aesthetic tendencies he shares with that generation in its incipient years, ca. 1948–1954. The first is the existential response to the Atomic Bomb, which engendered a passionate freedom and abandon on the part of these young poets and artists, leading to a total rejection of the authority of state and media, and all forms of materialism. The idea that everyone was potentially going to die tomorrow meant that you lived for today.

The second tendency was the new music: bebop. It was this music, and hipster speech surrounding it, that provided Ginsberg and Kerouac with an alternative cadence that freed them from European verse forms. About bebop, Belson told me, “It was simply the most radical thing at the time.”5 Along with his best friend, filmmaker and painter Harry Smith, Belson haunted the Fillmore jazz clubs in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Bebop presented a complex and variable field of polyrhythms and weird chromatics. The key to the music was that the rhythm was not regular, and each instrument occupied its own space, with a unique time form. It was a new conception of time and space and perfectly suited to the post-Atomic world, the “hydrogen jukebox” as Ginsberg wrote in a memorable image from Howl. It was a musical principle that would persist into psychedelic rock.

There were various means by which Belson and Smith adapted the structure and energy of bebop, but in the beginning the principal method was the calligraphic gesture, which had the added reward of interfusing their love of Japanese aesthetics. The final step was carrying these discoveries into the medium of film, where sound, image, and live performance made for a total art experience, one that would directly play itself out in the popular light shows of the 1960s. How fitting that Harry Smith should end his days in the Chelsea Hotel with the rent being paid by the Grateful Dead.

* * *

It is useful to consider how constructive a single effective mind can be in shaping the reality that others live in the world immediately around them. In the late 1940s and early 1950s Belson was very much at the center of a small but significant social and cultural matrix, located first in Berkeley and later San Francisco. It is primarily the poets of North Beach who are remembered today, such as Bob Kaufman or Lawrence Ferlinghetti, but Belson’s paintings and films speak to many of the same concerns, forging a new optics out of jazz, Indian philosophy, and of course the rigorous non-conformism that lies at the heart of the Beat sensibility.

In an interview with Scott MacDonald, Belson sheepishly acknowledges his place in the Beat scene:

SM: Were you Beat?

JB: Yeah, I was a Beat. As a matter of fact, I guess I’m just an old beatnik.

SM: Sunglasses, dark clothes…

JB: No, I think just an ordinary old man now, who you wouldn’t pay any attention to if I walked across the street. But at the time … we put on performances almost every night in the various little bars around here. And films were shown on occasion, in the bars and sometimes right out in the street, or particularly right on the glass fronts of the bars, or little underground showings, various places would be arranged and people would come to them. Sometimes fairly large, well-publicized events would take place and posters would be put up: poetry would be read, jazz would be played, and films would be shown. I personally never organized those things but I allowed myself to be shown under circumstances like that.6

* * *

In later years Jordan Belson took the role of artist-as-hermeticist seriously, becoming an almost total recluse in his last two decades to focus on his work, and his study of what Aldous Huxley called “The Perennial Philosophy.” Belson told his friend the filmmaker Paul Fillinger, “The archetypal images are true. They’re not just there in books. Anima, self, can be all experienced, especially when one gets past the ego level.”7 Belson compared the preparation of the mind via meditation as akin to a preparatory drawing.

The ego-based nature of the art world has certainly become a problem, where signature styles are often like name brands. “The ego fights for its own existence,” Belson observed. He considered silence to be an essential element to art, and often brought up the role of silence in the teaching of his favorite guru, Ramana Maharshi. “Maharshi refused to even sign his name after a point,” Belson noted. “Name and sense of identity can get in the way of self-realization.”

Every work he made, whether film, painting, tape compositions, had a ‘terrestrial’ dimension, and a metaphysical dimension, neither one being any more or less ‘real’ than the other, although film seemed to take him one step further towards immateriality. “Everything is a projection. Even the very heavens above are a projection no matter how impersonal they may seem. The gurus stop at nothing when it comes to this point.” Film was a medium that allowed him access to the purely experiential and abstract place he was seeking: the spectral unfolding of light and color in the present moment, a projection of his thoughts, a picture of his mind. On the other hand, film, no matter how independent, still required a maddening amount of interaction with commercial labs with little interest in helping him realize the artistic potential of the medium. After five or six years of filmmaking, having exhausted his patience (and available grants), Belson would retreat to paintings, pastels, small kinetic sculptures, etc. Then he would resume filmmaking. In this way, he would shift back and forth between film and visual art. Regardless of the medium the underlying impulse was the same: “Of course, even before I started making films, my paintings seemed to call out to be animated. Actually, I thought of them as animations in painting. I made a lot of sequential imagery where a form would go through some type of metamorphosis.”

While Belson was a much more sane and controlled person than Harry Smith, they engaged many of the same concerns throughout their careers. In 1953, after seven years of intense artistic friendship, Smith and Belson parted ways, never to reconnect. Smith pursued Crowlean magic and the occult, and Belson pursued yoga and meditation, both living out the implications of the same polyrhythms of syncretic cosmic structures. As Belson told Fillinger in 1977, “This realm is not divorced from the next realm. You can learn things in this realm that will carry over into the next one. You must condition yourself to see things that normally you would not see, that you normally would disregard.” Belson’s deep involvement in yoga for over three decades provided an inner world of imagery to draw on for his films and visual art. The training of entering that etheric dimension gave access to images resonant with that higher state. Images were realized more than depicted. “Matter out of non-matter,” as Belson once described it to me. The films and artworks were both the subject and object of his meditation, and for the viewer they were intended as objects of contemplation, presenting forms and images that shared an inner resonance with the ultimate ground of consciousness. As Belson told Paul Fillinger in 1979, “Meditation is the only sure way to know anything: being in touch with your own inner self/source will always give you the answer you need. Every life situation is a lesson if you have that going for you.”

Capturing these deeper inner states became an obsession for Belson, and the subject of much of his life’s work. He did not like the fact that artists were seeking money and fame rather than selflessness. He had no desire to show his artwork in a commercial setting; and so, as he made it, he lived with it briefly, showed it to a few lucky friends, and then carefully packed it away into a closet where it would remain for many decades to come. In retrospect, the small room that Belson occupied now takes on an infinite dimension.

03/06/2023