You have no items in your cart.

While the other kids were playing marbles or collecting Joe DiMaggio baseball cards, Harry Smith was becoming an amateur ethnologist. When the Oregon-born, Washington State-raised son of a cannery family was still a teenager, Smith jury-rigged a cheap recorder to a big battery. He captured the rituals of the Pacific Northwest’s indigenous Salish tribes as best as his crude technology allowed, a little Lomax of the left coast.

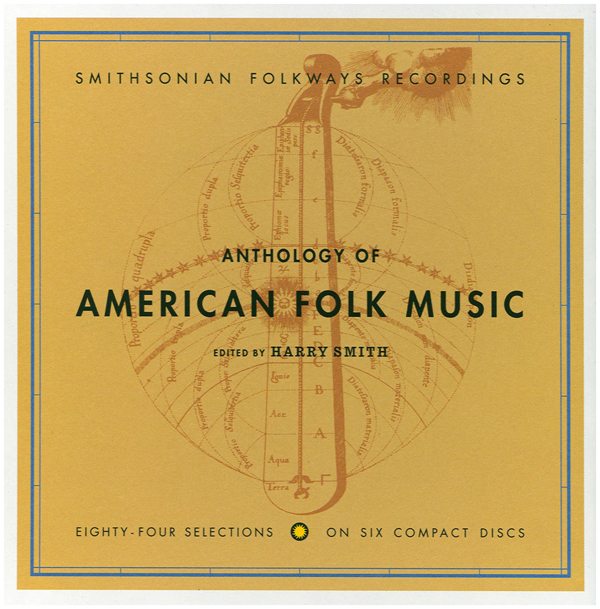

In the months to come, he swooned over the rest of his country’s early recorded legacy when, in 1940, a 78 RPM single by Mississippi bluesman Tommy McClennan arrived at a record store along the shores of Bellingham. Smith was haunted by that sound, obsessed, hooked. He wanted more of this American folk music. The bombing of Pearl Harbor soon gave it to him. After the attack, when the United States joined the Allied forces in Europe, old-timers dug out their shellac phonograph records at the military’s command. Some would be melted down for weaponry, others dispatched to entertain “our boys” on faraway bases. Old record warehouses cleared their shelves to make way for fighting supplies. If you could get to it in time, you could amass the entire recorded history of the United States for peanuts. Smith wasn’t going to war. His bowed skeleton and stooped frame caused by a childhood case of rickets made him unfit for duty. Instead, after moving to the San Francisco Bay in the early ’40s, he went shopping. He bought abandoned troves of “hillbilly and race records” (crassly commercial terms he perpetually resented) and even met Sara Carter—the captivating voice behind the transformational Carter Family country records he adored—a few hours east in a trailer encampment. For a decade, he amassed thousands of records that made their way to California from all points east—“immensely protective of the record collection and greedy about getting more records,” an old chum later described him, with love. An associate of the emerging Beatnik resistance, Smith was also a burgeoning visual artist, fastidiously illustrating strips of film to run back through a projector; in those early days of LSD research, the results suggested astral phantasms, beyond the limits of reality. Heavyweights like Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk jammed to his work and he to theirs, especially Dizzy Gillespie. He’d make intricate abstract maps of their pieces, hundreds of colorful little curves and geometric artifacts. When German aristocrat and eventual Guggenheim Museum cofounder Hilla Rebay offered him cash to continue this work in New York, he crossed the continent as the innocent ’50s dawned, all conservative and safe and potentially very boring. But the money—as always with Smith—wasn’t enough, whether for the drugs he loved or the films he loved to make with them. So Smith sought out a record label head by the name of Moses Asch to buy thousands of his records. Smith needed cash more than shellac; Asch demurred. His finances, after all, weren’t exactly stable. Only four years earlier, his first label had cratered, sending him into bankruptcy. Because of those legal woes, his longtime secretary, Marian Distler, registered alone as the president of an all-new label, Folkways, never even mentioning Asch in the paperwork. Distler and Asch were surviving on $25 per week. Rather than spend a fortune he did not have, Asch presented Smith with a counterproposal: The 33 1/3 LP was steadily gaining post-war popularity, so why didn’t Smith comb through his 78s and pick the most compelling tracks, the most gripping documents of American folk? If Smith would sequence them, Asch would issue the results with the imprimatur of his young Folkways imprint. Folkways had already released strong sets of Southern rags and blues and East Tennessee gospel, and others had released troves of folk elsewhere. But Smith, Asch later said, understood this music’s “relationship to the world.” He could do it better. And so Smith—a struggling 28-year-old artist who embraced the occult and sometimes insisted Aleister Crowley was his father, new to New York from the Pacific Northwest—made a mixtape, largely documenting the struggles and songs of the American Southeast. The Anthology of American Folk Music, originally released in August 1952, collects 84 white-hot cuts of early blues, country, gospel, Cajun, cowboy, jazz, jug, and dance, jumping across those supposedly color-lined genres with revelatory aplomb. These songs were only a couple decades old when Smith repurposed them; they were so strange and uncanny, listeners assumed the artists were dead. In effect, Smith had reached across the lacuna between the Great Depression and World War II, a period when vinyl sales cratered almost entirely, and pulled an almost forgotten past back into the country’s present. Some tunes here read like ill-informed news summaries of the Titanic’s disaster or presidential assassinations, while others are emphatic paeans to a ferocious and feared god. One man vows to run away with his love forever, while many others share dastardly deeds of betrayal, cheating, and murder. There is dying and dancing, working too hard and working too little, fucking and fussing and fighting, all tucked into four wonderfully overwhelming hours. Smith split his mix into three broad sets of about 28 songs each. Each set got a symbolically colored cover, the hue tapped from his lifelong interest in alchemy—green “Ballads,” for water; red “Social Music,” for fire; and blue “Songs,” for air. There’s been much ado made about his intentional track-to-track connections, how a lyric or an idea from one song arrows into the next. Look for such links, and you’ll often find them. Instead, I recommend letting the Anthology wash over you as a whole, revealing a world where anything could and often does happen. When he spent time with the Salish tribes in his youth, he recognized his interest in “music in relation to existence,” how sound could mirror the mercuriality of life. This was that realization’s triumphant apotheosis. But Smith didn’t stop with the music. When he trawled the scrap heaps and record shops in the ’40s, he collected record catalogs from stores and started tracing the songs to their sources, using the pioneering musicology of Cecil Sharp, the Lomax family, Olive Dame Campbell, Carl Sandburg, and the like to tease out their Appalachian, Delta, and even Transatlantic origins. In a 28-page book that accompanied the Anthology, Smith did his best to reveal those roots, his sources, and anything else he knew about both song and singer. He brilliantly reduced each number into an irreverent newspaper headline, too. Of “Ommie Wise,” a fiddle-backed murder ballad so tragic it may be the set’s heaviest wrecking ball, he riffed: “GREEDY GIRL GOES TO ADAMS SPRING WITH LIAR; LIVES JUST LONG ENOUGH TO REGRET IT.” The liner notes—themselves an essential document of American musical intrigue— incorporated cut-and-paste photos of the performers, their instruments, sheet music, and how-to banjo schematics. The set’s cover, meanwhile, audaciously included a 16th-century sketch of the “celestial monochord” by Theodor de Bry, the European illustrator who gave Europe its earliest glimpses of the New World. It was said that the very hand of God reached from the heavens to tune it, divining all music, no matter the origins. Smith’s Anthology represented his syncretic vision of the world, unbound by genre or class or concepts of high and low art. Mississippi John Hurt, the Alabama Sacred Harp Singers, and Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, quoted by Smith in the liner notes, belonged in conversation, not distant cultural corners. What’s more, 1952 was the middle of McCarthy’s Red Scare and the dawn of the Civil Rights movement, when the communist-linked Civil Rights Congress accused the United States of genocide against Black Americans in front of the United Nations. The Anthology offered a potent if tacit political message through Smith’s idealist vision for the United States. Much like Woody Guthrie, Smith saw his country as it was but did not let that interfere with his hopes for how it could be. He never listed the race of these performers, an uncommon move in those days of unabashed Jim Crow, himself a byproduct of American folk minstrelsy. He deliberately omitted any song that included a racist epithet, a fact that became painfully clear when the label Dust-to-Digital initially included them in a 2020 companion set. Smith relished the fact that people thought Mississippi John Hurt, born near plantation land at the end of the 19th century, was a white hillbilly. This was America reimagined for the future, molded from the scraps of its barbaric past. Perhaps this hope is why its signal keeps coming around again and again, like some lighthouse’s beacon. After its initial release in August 1952, it unsteadily emerged as a large piece of the foundation of the folk revival of the ’50s and ’60s, the movement that gave us the songwriters who reshaped the possibilities of rock and, by extension, all that followed. It was one of the first albums the White House acquired for its official record collection in the early ’70s, a bit of terra firma during the vertiginous Nixon years. The monumental CD edition issued by Smithsonian Folkways in 1997 (the venerable institution acquired Asch’s label and all its 2,168 releases a decade earlier) sparked a subsequent renaissance, allowing the old sounds of American folk to follow unexpected new courses. A slapdash, pricy, and coveted LP rendition by Mississippi Records in 2014 had less widespread impact, but it looked gorgeous. After 70 years, to hear this Anthology of American Folk Music is still to hear what you already know about the United States, our collective tangle of sadness and celebration, promise and failure. To really hear it, to understand the radical depth of the world Smith was trying to conjure, is to know that we could and can perhaps still be something better. FORGOTTEN FOLK SONGS SWEEP UP INNOCENT BYSTANDERS, TRANSPORT THEM TO HEAVEN AND HELL, TURN THEM INTO MOLES BENEATH MOUNTAINS. The critic Greil Marcus—an Anthology enthusiast so unabashed he once rendered the set’s characters into an imagined soundstage town dubbed “Smithville” to the apoplectic dismay of John Fahey—once called its 61st song “the greatest recording ever made.” By that point, in 2010, Marcus had been writing about the Anthology for well over a decade, his essay “The Old, Weird America” even serving as the analytical gangplank for the 1997 reissue. His pick was “James Alley Blues,” one of the six tunes that New Orleans toughie, bluesman, and boatman Rabbit Brown cut in 1927. And it is a masterpiece in miniature, the bent-and beaten strings of Brown’s tinny guitar the wobbly framework beneath his existential crisis. He desperately loves a woman who is exploiting his country naivete, using him for rent, groceries, and, it seems, goodness at large. “Times ain’t now nothing like they used to be,” he bleats at the beginning, his voice trying but failing to get bigger than a moan. Is there a more concise summary of a curdling relationship, of the creeping suspicion that a love isn’t worth all the worry? By the song’s end, Brown doesn’t know if he should kill or kiss this source of agony. You just want him to run, to find someone who wants to be his “daily thought and nightly dream.” There are at least a dozen songs on the Anthology that still dazzle me the way “James Alley Blues” dazzled Marcus when he wrote that in 2010, even after my own couple decades with them. I hear them and think that nothing could get better, that no one else has ever captured the essence of emotion or joy of sound so completely. This feeling lasts, at least, until the next good gobsmacking. In fact, throughout the Anthology, there is the wonderful feeling that any of these songs might at any moment feel like “the greatest recording ever made.” Despite Anthology’s idiosyncratic artistry or all the through lines to follow from these century-old tunes, its nucleus remains these 84 songs. There was, after all, not yet a music industry about which to be cynical, no real precedent for being disaffected. Here are 69 acts forging blindly into the frontier of recorded sound, supercharged by the wide-open novelty of the whole notion. Take, for instance, the 63rd song, Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s 1928 recording of the near hallucinatory “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground.” Lunsford was a singing lawyer and avid song collector from a nook of the North Carolina mountains that, a century later, remains economically and socially sequestered; in 1949, nearing 70, Lunsford recorded a staggering 330 songs in a two-week spree at the Library of Congress. This, though, is his triumph. Sturdy but strange, like the burl of some mighty oak, his voice is perfect for this string of seemingly simple but altogether surreal images. He wants to be the rodent that topples the mountain, then the charming lover gifting his gal a “$40 bill,” which had not existed in the United States by that point for more than a century. He is a lawyer who talks about busting out of the pen, the sun-bathing lizard who somehow hears his darling sing. These incongruous images are an inheritance of the local oral tradition, but taken together, especially above Lunsford’s spring-loaded banjo, they shape an endless mystery. What does Lunsford want me to do with these warped vignettes? Fight the power? Relax and enjoy life? Give up on life altogether? Here is a riddle with no right answer, presaging abstract expressionism with little more than a few strings. That sense of mystery is the locomotive behind many of these other “greatest recording[s] ever made.” Just what happens to “Frankie,” who shoots the scoundrel she’s been supporting after he repays her by cheating? Above one of the most enchanting guitar lines ever committed to shellac or any other format, Mississippi John Hurt doesn’t plainly say. And is Clarence Ashley’s take on the Appalachia-via-England standard “The Coo Coo Bird” the forlorn testimony of a ghost or the doubtful dreams of an ordinary American aspirant? In Ashley’s haunted hums and twitching banjo, I can hear it both ways. The pleasures are as far-flung as they are absolute. Backed by two trotting guitars, the fiddle of Texas Prince Hunt is so fierce during “Wake Up Jacob” it recalls a scintillating Eddie Van Halen guitar lead or a splenetic Kathleen Hanna vocal. Once in my life, I want to feel what Hunt’s feeling, or at least how he’s been feeling it. Not so much, though, with G.B. Grayson and his exquisitely heartsick “Ommie Wise.” His fiddle sobs intermittently as he relays the real-life tale of Jon Lewis, who murdered Naomi Wise, a lover whose only crimes were sweetness and trust. He escapes into the Army, presumably to get paid for his violence. The weight of it all bends Grayson’s voice until it starts to break; his fiddle is all elegy, tears down a ruddy cheek. From start to finish, Smith’s sequence of early gospel recordings—the second half of “Social Music”—is rapturous. I don’t know that I’ve ever heard someone sing with more force than Chicago’s Rev. Sister Mary Nelson, whose gutbucket warnings of the Second Coming are amplified by the innocence of two kids who chase her lead. Likewise, the growl and bark of Blind Willie Johnson, clenched so tight you may mistake the scriptural snippets of “John the Revelator” for nonsensical syllables, is countered by the seraphic tone of (possibly) his wife, Angeline Johnson. Heaven may be the goal, the juxtaposition seems to say, but you’ll need to endure hell to get there. Of course, there are misses, songs that may make you wince the first (or last) time you hear them. Even Smith lampooned the set’s gambit, “Henry Lee,” a tale of murderous love and unrequited lust delivered so drably it makes the side-effect disclaimers at the end of pharmaceutical commercials feel inspired. I likewise tire of its successor by the Alabama duo Nelstone’s Hawaiians, more concerned with fumbling through a poor imitation of slack-key exotica than digging into this tale of child abduction. Or is it murder? Rape? They’re too noncommittal to offer insight or intrigue. Pop and Hattie Stoneman, who helped pioneer and popularize country music, remind me that someone’s influence can sometimes outstrip their art. Their two tracks here presage the worst of twee. The couple’s back-and-forth relationship banter is more cloying than old-fashioned rock candy, their preening recitations of courtship about as seductive as a box of rotten chocolate. That’s the joy of any mixtape, made clear here for perhaps the first time. You can hear through someone else’s ears, take what you love and leave the rest. Some have made bloodsport of despising “The Lone Star Trail,” a cowboy’s travelogue softly strummed by Ken Maynard, a Hoosier who liked to say he was from the contested banks of the Rio Grande. He sings of the plains, his dreams, and his duties, pausing for a chorus where he coos like a coyote. Smith vaunted this as “one of the very few recordings of authentic ‘cowboy’ singing.” Critics have lampooned it as a pandering precursor to self-proclaimed folk musicians who know nothing of rural life. I’m with Smith here. It’s one of his Anthology’s very few stoic treasures. And when the moon is just right, I swear it may be the greatest recording ever made. A MADMAN’S MIXTAPE FINDS ITS PEOPLE IN DRIBS AND DRABS! THEIR MUSIC RESPONDS IN KIND. David Fricke wrote in Rolling Stone that it is “impossible to overstate the historic worth” of Smith’s Anthology. John Fahey, always a master of exaggeration, opined that it would hold up against “any other single compendium of important information ever assembled,” Dead Sea Scrolls included. Indeed, Smith’s masterwork is perhaps the most important American mixtape ever made, at least until the dominance of hip-hop decades later. But its influence did not arrive as some sudden sea change, an instant and undeniable transformation. To wit, researcher Katharine Skinner has published intriguing work about how little the Anthology sold upon initial release, disappearing “from the market altogether for several years” and never even cracking Folkways’ internal best-sellers charts. This canonization, Skinner argued, did not comport with the mixtape’s commercial reality, at least before the Smithsonian’s ballyhooed 1997 edition. Skinner’s findings fascinate me, not as a counter to the Anthology’s influence but as a suggestion that its spread, at least after the original 1952 release, was often an act of community, not unlike much of the music itself. Several years ago, while flipping through a record store’s used bins, I found a very early pressing of the Anthology’s spirited second volume, the records scuffed with love but perfectly functional. It felt like a talisman; more important, it felt instructive. Housed in a thick plastic case, stamped with the old organizational tags of a local library, my find had once been a community resource, forked over to now-unknowable people who were interested in such songs and, just maybe, went on to start a band of their own. “It was the beginning of the folk revival, everyone playing guitars,” Alice Gerrard told me late last year, in an interview for The New York Times, of her arrival at Antioch College in the early ’50s. “My friend, who became my husband, gave me—no, loaned me—his copy of the Harry Smith Anthology. That blew my mind, so I started looking for other things.” Gerrard went on to start a canonical duo, Hazel and Alice, that at last centered women in old-time and bluegrass circles and, in turn, helped center women like the Judds in country. (The first song the Judds learned? A Hazel and Alice number.) The line between Smith’s low-selling compilation and, say, the chart-topping songs of Judds zealot Kacey Musgraves is long but direct. How many times did that happen? How often is it still happening? It’s hard to say. Bob Dylan, for instance, has waffled about how much the Anthology inspired him, but he has talked about the way friends shared their copies. Bellowing Greenwich Village fixture Dave Van Ronk owned the set, Dylan admitted in 2001, so he and friends would hang out at people’s houses and listen. His “Hard Times in New York Town,” from 1961, is a faithful re-creation of the charged “Down on Penny’s Farm,” Smith’s 25th selection. Dylan simply swapped the scenery of the country gripe for his new city. Maybe Dylan learned of the duo whose members’ names remain unknown somewhere else, but Smith seems the most likely provenance, especially given how often bits and pieces of the Anthology peppered the next 60 years of his work. There is a pernicious tendency to overstate the isolation of these performers, to treat those living in Appalachian hollers or Delta hamlets like hermits, sealed off from the rest of the world by design. But Anthology’s works were powered by community and connection, resulting from an exchange of ideas by its itinerant preachers, Hollywood actors, and bona fide party bands. Lunsford, the giver of the $40 bill, collected tunes as he moved across the peaks and valleys of the Blue Ridge. Charlie Poole and Kelly Harrell, who sing separate songs about dead presidents on the Anthology, labored in Piedmont mills, hardscrabble and dangerous places where music was a necessary social balm. They even recorded together. Indeed, many songs on the Anthology are magpie masterworks, three minutes of magic synthesized from a half-dozen different sources. The residents of Smithville weren’t intentionally distancing themselves from society; they were trying to sell records. A few became some of the country’s first music superstars, while others still linger in near anonymity. Take “Moonshiner’s Dance Part One,” an ecstatic medley of children’s tunes, romantic ballads, polkas, and gospel songs crammed into 160 breathless seconds by a party band in a St. Paul nightclub. The group, Frank Cloutier and the Victoria Café Orchestra, was a near-complete enigma until 2006, when relentless Anthology researcher Kurt Gegenhuber tracked down their census records and recording credits. They tried fitting the entire world into the sides of a 78. Interaction and recombination, not isolationism, is the true spirit of Smith’s Anthology. As an audience, we’re closer to this message than ever. The first folk revival the Anthology helped spark in the ’50s and ’60s could certainly be conservative, with hordes of stand-and-deliver folkies just trying to give us some truth, man. (Dylan became Judas to the lot for simply indulging in electricity.) The next revival Smith helped usher in—after the Smithsonian reissued the Anthology in 1997, six years after his death—better actualized his syncretic vision. Having already inherited the liberation of rock in all its variants, plus free jazz and electronic music, this generation heard in the Anthology new fodder from an ancient fount. They ran with it, headlong into alt-country and freak-folk and a few dozen assorted permutations. “It should be free and exhilarating … convey something of the wildness and wonder of existence,” English singer Sharron Kraus wrote of modern folk music in a stirring essay about the Anthology. She traced the ways it helped compel her to move to Philadelphia and join a community that had taken the set’s engrained strangeness as its cri de cœur. “It should open us up to unfamiliar worlds as well as familiar ones.” The music of that fertile moment, inspired in part by Smith’s work half a century earlier, still sends out ripples. I now see that same unencumbered enthusiasm for putting disparate pieces together, for making the old new again, in online collage culture, a spillway of wild hybrids. Smith, I think, would have tried to collect the entire Internet and then yelled, with his wild grin, “Look at what I have found!” He wasn’t committed to protecting anything. He was committed to possibility. 84 SONGS TELL US WHERE WE WERE A CENTURY AGO. THEY TELL US WHERE WE ARE, TOO. Soon after the start of the year, I commenced another rambling road trip across the Lower 48, the only states that existed when Smith made his mixtape. From California through Texas and out to Tennessee, and eventually north to Connecticut, I played his entire Anthology—at maximum volume, until my van’s speakers crackled like the horn of a vintage Victrola—on repeat for the first time in years. I spent 4,000 miles with it, thinking about the modern United States unrolling in front of me and the century-old nation rattling out of my stereo. They felt shockingly similar, the topics Smith’s set tackles not only relevant but present at more highway crossings than not. “They cover such subjects,” ran the 1952 Billboard brief announcing the compilation, “as love, murder, robbery, politics, gambling, travel, prison, the Bible, courtship, hunger, etc.” Let’s unpack that “et cetera” to include unemployment, adultery, agriculture, industrialization, and beguiling rural weirdness. There is an abiding ethic of American restlessness to the Anthology, too, someone always going somewhere. They’ve grown tired of the country or jittery in the city, itching for a better lover or a new beginning altogether. It is music for moving on, toward some destiny you have simply yet to manifest. Uncle Dave Macon’s electrifying “Way Down the Old Plank Road”—complete with the startling admonishment to “Kill yourself!”—documents being put on a chain gang simply for getting drunk, for existing freely. I passed near Mississippi’s infamous Parchman Farm and multiple road signs warning of hitchhikers that might be escapees of nearby penitentiaries, extant symptoms of the same carceral state against which Macon railed. And he was so white he was dubbed “The Dixie Dewdrop.” Blind Lemon Jefferson sounds like he’s singing for his sanity during “Prison Cell Blues,” especially when he hollers about the apathy of his captors. “I asked the government to knock some days off my time,” he sings, stretching that last word like a wail. “Well, the way I’m treated, I’m ’bout to lose my mind.” There were mega-churches and little country sanctuaries along the way, all preaching pacific or prosecutorial strains of Christianity you can trace on the Anthology. There was Cadillac Ranch outside the city of Amarillo, then its more esoteric and funny country cousin, Slug Bug Ranch, in the small town of Panhandle, just to the north. They both reminded me of the wild ways folks find to entertain themselves, as eccentric as “The Coo Coo Bird” and enjoyable as Henry Thomas’ joyous taunt, “Fishing Blues.” I saw the lights of farmers’ tractors blinking in the distance long after dusk and long before dawn, reminding me of the Carolina Tar Heels’ great country trot “Got the Farm Land Blues,” about the endless frustrations and travails of raising crops for a living. And it was hard not to think about the Tar Heels’ labor lament “Peg and Awl”—the tale of a longtime cobbler whose job has disappeared because a new machine that “make 100 pair to my one”—in truck stops, where drivers worried about the automation that may soon gobble their gigs, too. Vitriolic politics spilled off the front pages of local newspapers there, just as they did with the Anthology’s two songs about two presidents killed by a disgruntled man and an energized anarchist, respectively. Most nights, delirious with white-line fever, I’d crawl into bed and watch a little Dateline, tales of cheating, robbery, and murder stuffed neatly into hour-long blocks. I couldn’t help but imagine how Buell Kazee would have told those tales in his adenoidal voice, or G.B. Grayson above his forlorn fiddle. Delight through other people’s worst moments? Sometimes, I swear I wished I were a mole in the ground, too. There is little point in limning all that has changed about the United States, the advances we have made technologically, socially, and legally. But as I listened to Smith’s assemblage again and again, I couldn’t help but think that only the stitching had been replaced, not the fabric itself. “I’m glad to say my dreams came true, that I saw America changed through music,” Smith said at the 1991 Grammys, nine months before his death, leaning against the podium like the king of cool. Sure he did, but exactly how much? I have long struggled with the name Anthology of American Folk Music, for the completism and inclusion it suggests but to which it never actually aspired. Smith worked within very specific parameters here, pulling only from commercially available recordings made in real if rudimentary studios between 1926 and 1932. He made field recordings of indigenous Americans during several phases of his life, but neither field recordings nor indigenous Americans are here. And neither are there many women nor much music from the North, the West, or the Midwest. Such records hadn’t flooded the market to the same degree as these raw transmissions from the South, the country’s unqualified musical Eden. The Anthology represents, at most, a cross-section of the whole of American folk music, and that fraction gets smaller every year. As vital and urgent and engrossing as these pieces are, they are collectively a synecdoche for the enduring American condition, forming an anthology of American experiences from bits of our musical history. Smith intended to compile five, maybe even six volumes of the Anthology; a natural polymath, he instead spent the rest of his life making films, collecting things like paper airplanes and string games, and becoming the de facto mayor of the Chelsea Hotel, where he encouraged young artists like Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe. Fahey’s Revenant Records eventually finished the fourth volume, a year before the death of the guitarist and Anthology adherent. After three volumes, what else did Smith have left to say? You can’t stream the Anthology, not out of some Luddite resistance but likely because the legal bureaucracy of gathering together these 84 tracks remains imposing if not altogether impossible. (You can, at least, currently hear about half of them on Spotify.) You can sample 30-second bits of everything and download the 1997 liner notes through the Smithsonian’s marvelous website. Or you can buy the 6-CD box set for $80, a hell of a federally subsidized deal. But I think that Smith, forever in need of someone to float him more than a few bucks, might actually want you to steal it, to grab the whole thing from the Internet Archive and dig in for the rest of your life. The Anthology was always legally suspect, anyway, released by Asch with the hope that larger labels would not care about the passion-driven reissue of sides they’d long ago let drift out of print and into obscurity. The Smithsonian, it’s worth noting, worked through these legal issues for its attentive reissue, prompting at least one critic to say it fit our “benign, Disneyfied version of the twentieth century.” He has a point. This music was a positive piece of our national inheritance, Smith always seemed to say. Someone might as well take a risk sharing what good came with so much bad, particularly if they could front him the cash.

02/05/2023