You have no items in your cart.

Harry Smith is known mostly through his seminal collection of American folk tunes from Folkways Records, The Anthology of American Folk Music, which earned him recognition after its original 1952 release and, again later, with the folk revival of the 1950s-’60s. Without Smith’s recordings and his insightfully elaborate notes for the songs, the landscape for American music would have been dramatically weakened. Smith, according to his own design, had intended for the Anthology to be a ticking time bomb of American music, culture and social justice. In a 1969 interview with John Cohen, Smith said, “I thought it would develop into something more spectacular than it did, though. I had the feeling that the essence heard in those types of music would become something which was really large and fantastic. In a sense, it did in rock-n-roll.”

At a very early age, Smith worked in other fields such as cultural anthropology/ ethnology. After his untimely arrest for suspicion of robbery, he met two informants who directed him to some Kiowa peyote singers. Smith stayed on for over a month and put together a collection of songs with explicit field notes and annotations, eventually producing a 1965 (not released until 1973) record for Folkways that led back to his original interests. The Kiowa Peyote Meeting-an assemblage of field recordings Smith collected after his ill-fated attempt to work for Conrad Rooks in Anadarko, Oklahoma on his film project Chappaqua (starring, among others, William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg)-is the first known recording of peyote singers from North America. Late in life, Smith felt that his recordings of the peyote songs were one of his greatest accomplishments. In the same interview with John Cohen, Smith defends his pride in the peyote recording above his Anthology, “The peyote record is important because it represents some kind of comparable breakthrough, in that someone was willing to pay for such elaborate exposition of a very obscure subject.”

But Smith’s story starts long before 1965. In the 1940s, Smith had already begun the task of field recording and researching Northwest Native American tribes near his home in Bellingham, Washington. A childhood friend of Smith remembers him being way ahead of his time. Bill Holm, the Emeritus Director of the Burke Museum, the University of Washington’s museum of archaeological and anthropological collections, knew Smith as a teenager and attended many of the same Lummi and Swinomish ceremonies. Erna Gunther, who was a student of the famous ethnologist Franz Boas, introduced Holm to the already scholarly focused Smith. Though the friendship was brief, it helped influence Holm’s future as a scholar and anthropologist. “He [Smith] was way ahead of many trained anthropologists,” Holm said, “and the loss of his notes and probably most of his pictures [while researching local tribes] is tragic.”

What little remains of Smith’s supposed “massive” research and archive is on collection at the University of Washington Library-a four-album compilation of sound recordings with extensive field notes and drawings, a few photos and a couple of Kwakiutl artifacts.

Holm also sheds light on Smith’s family, saying they came from a long line of eccentrics and scholars. “Harry said his grandfather had collected the pictographic autobiography of Sitting Bill, now in the National History Museum of the Smithsonian Institution. In fact, acquired it from a lieutenant he knew, and it was his father, Robert A. Smith, who gave it to the Smithsonian,” which all turns out to be true-his grandfather played a huge part in giving us one of the greatest American biographies, that of Sitting Bull.

Smith’s earliest interests in anthropology and music led him to the field to conduct sound recordings in the nearby areas of his childhood home. The coastal ranges of Oregon and Washington were, in many respects, the last remaining areas whereindigenous people had minimal contact with the new emerging American West. Between Harry’s father, who apparently had an interest in the occult and taught Smith as a boy how to draw the Tree of Life from the Qabalah, and his mother, who taught on the Lummi Reservation, it seems that his parents encouraged such particular interests.

NAROPA DAZE

It all started out innocently enough-all I had to do was bring his soup at 12 o’clock from the Naropa Café to his run-down apartment on campus. Allen Ginsberg had brought Smith to Boulder, Colorado in the summer of 1988 in order to get him out of his cramped lower-east side apartment. Smith always referred to Boulder as the “Holy City” due to its politically correct, New Age façade and endlessly poked fun at Naropa-its poets, its Buddhists and, in general, Boulder’s lack of edge.

Although Harry grew up in a fairly small town in northern Washington, after he left the Seattle area for Berkeley, and later San Francisco, he was a product of the city. Boulder was a respite from New York City, where Smith had lived since 1950. Harry knew poverty much of his life during the ’70s and ’80s in New York, but, by comparison, he was doing pretty well in Boulder and things seemed to be improving. His health strengthened, he gained weight and a grant from the Grateful Dead’s Seva Foundation that Ginsberg helped to secure all were positives for Smith.

He also began working on various projects. He prepared lectures he would later present during the summer writing programs-1988 on Surrealism, 1989 on Alchemy and ’90 on Native American Cosmography. Smith recorded thousands of hours while at Naropa as part of his sound compilation of Boulder. He also began work with Nina Paul, who was a student of Stan Brakhage, on a new film project-which would have been his last. The working title was Keys, and it was to resemble the animation techniques found in Heaven and Earth Magic, with hundreds of cut-out keys he had collected and xeroxed from numerous books he had collected.

Chuck Pirtle, a friend from the MFA writing and poetics department, planned to be away during the semester break and asked if I would help look after Harry for a month while he was gone. Harry and I proceeded to get very high and discuss a range of things-the Northwest (where we both grew up), music, poetry, painting, ethnology and cosmography. The winter of 1989-90 hit Boulder with heavy snows, though, and I ended up looking after Harry over most of winter break. Since I must have stopped by at least once a day during that time, we began to strike up a friendship. And due to the fact that we both had originally grown up in the Northwest, we had much to talk about.

The campus was completely quiet during that latter part of December, and Harry was one of only a few people in the campus housing area. Although he was feeling better, he was still quite fragile. Entering his place was like no other experience I have ever known. One was not to touch certain books or sit in places that were not designated by Smith himself. His fridge contained road kill and other undesirable mold cakes. There was cat shit throughout the entire bathroom floor and tub. We came by periodically to help clean and stock Harry up on things like baby food(which he could only stomach when he first arrived in ’88). After a few visits, Smith’s apartment had become the stopover before or after a class. Along with the carnival-like feel his apartment took on, Harry had slowly amassed a group of us who went in to hang out, assist with errands and basically spend time talking. He must have been interviewed at least twice for student magazines and was more often referred to as the campus gnome.

He was not easily convinced to change anything about who he was and what he did-wherever he landed. For example, one summer when he played the King in Marianne Faithfull and Hal Willner’s production of the “Seven Deadly Sins,” midway through the performance Smith lit a joint on stage at Naropa’s sold-out performance. He mostly went unchallenged while at Naropa and got away withpretty much anything he wanted to do as campus philosopher, shaman and sometime lecturer.

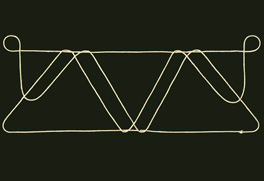

Our time together culminated in a couple of interesting projects. Harry had asked that a friend and I spend most of the Summer Solstice of 1990 together and tape our whole afternoon and evening. It seemed like a fun experiment and another great excuse to be around Harry and his random experiments. Although I haven’t heard it since, it was one of my fondest memories with Harry. The last project was his allowing me to use four of his drawings for my first chapbook of poems, Methane Cocktail. He was drawing border art all the time and had really done some beautiful pen and ink works. I used one for the cover and three other pieces. I was a little shocked but also excited that he would allow me to use his work, considering his obsessive nature about his books and other projects. After giving a copy to Ginsberg, Allen seemed perplexed and asked, “Harry let you use his work?” Soon after the lecture, Allen made his way over to Harry’s place-book in hand. Either Allen wanted to have Harry sign it or ask what the hell he was doing giving his work away to Naropa writing students for free.

Soon after I left Oregon prior to a semester abroad in Nepal, I talked with Harry at my parents’ home in Eugene for what would be our last conversation. He asked that I bring back a musical instrument of some sort-nothing fancy, something off the streets. Although I ended up buying a handmade street fiddle in Katmandu from a kid for 500 rupees, I was never able to get it to him and it remains a fond remembrance of our brief time together in Boulder.

TEENAGE ETHNOLOGIST

I met Harry at the Swinomish Smokehouse near La Conner, [Washington]. It was 1940 on Treaty Day (nearest weekend to January 22nd, the anniversary of the Point Elliott [Mukilteo] Treaty of 1855). I was along with a group of University of Washington anthropology students led by Dr. Erna Gunther. She regularly took groups of students to the Winter Dances, something that could not be done in recent years, probably since the 1940s. These dances are considered sacred activities, and are much more closed now than then.

Smith’s last lectures during the summer of 1990, “Native American Cosmography,” ironically bridged back to his earliest days in the Puget Sound area. He reminisced about Winter Dances and Spirit Dances he attended fifty years earlier at the age of 17. Sifting through those tapes, it helps to see what stood out in Harry’s mind after that many years of recollection. What many believed was mere conjecture and the stretching of the truth has turned out to be mostly true. Smith did attend theseWinter and Spirit Dances and was allowed to enter these ceremonies at a time when they were certainly open but not always accessible to someone his age.

These ceremonies were not mere celebrations of various tribal songs, but were actually rituals where the dancers and singers were taken into a trance state. Even with Holm’s and Smith’s early knowledge, it must have been slightly intimidating for them to be attending and recording these events at their age. These momentous events of Smith’s youth surely transformed his worldview and, later, his contribution as an artist.

Harry was ultimately fascinated with how people transcend this physical world. He sought this out early on with his discoveries of the Spirit Dance, as well as his own experiments with peyote and other mind-altering substances. For Smith there was always a deeper connection, a mystery to be figured out or journeyed upon. Even with his last lectures, he discusses his fascination with the use of hallucinogens.

What is evident is that, after forty years, he was hugely steeped in ethnology and animistic cultures. A fragment of the two-volume resource book for the lecture contained readings from sources such as DeVereux’s “Mohave Ethnopsychiatry and Suicide, “Obscure Religious Cults” in Cosmogonical and Cosmological Theories and Amazonian Cosmos, to name a few. In a way, he never really stopped being that teenage prodigy ethnologist. He only tweaked and added to his elaborate experiment.

After Nepal, I eventually settled in Seattle and began co-editing what would later become Smith’s Selected Interviews. Eventually my editing led me to the University of Washington, where I came across the remnants that Smith had left behind prior to his move to the Bay Area to pursue a painting/film and academic career. Smith had hoped to work with anthropologist scholar Paul Radin in Berkeley, according to Jordan Belson.

By the mid-forties, Harry had already assembled never-before-heard northwest coastal tribal music and folklore long before he sought out the editing of the Anthology of American Folk Music. He had certainly amassed a large collection of 78s by this time, as he remembers so well in his early and late interviews. He even remembered where he bought his first Buell Kazee records in Tacoma. Other tidbits that have not been entirely sifted through include his working at Boeing Aircraft in order to pay his tuition at UW, his being a teaching assistant while at the University and his interests in the various schools of occult thought.

We certainly do not know all of what occurred in Smith’s younger years in the Puget Sound, but we have a clearer idea of what his early motivations were and that, from 1939 through 1946, Smith collected a large amount of photos, recordings and artifacts. It is obvious that Smith decided what his following was to be.

Through years of investigation, curiosity and creativity, Smith had distilled and condensed a way of being and assembling life that is unmatched in the last century.He derived a way or method of expression that constantly found correlations andpatterns. The system he incorporated resembled, in many ways, alchemy or Qabalah more than an artist cultivating his own style and mode. What had begun as an early obsession eventually led into a hermetic synthesis-Smith pulled every shred of information into a fabulous realm of possibility, and now the pieces are laid out for our own challenging benefit.

Maybe it was all hindsight and recent media has made too much out of Harry’smusical contribution, but it is clear to most that Smith’s Anthology struck a deep chord in the American vernacular. Ironic that a generation later his films would be blasted on walls in the Bay Area for acid parties and Be-Ins-and now Smith’s films are played at Rave’s and other film and musical events all over the world. Smith’s influence is a work in progress as it pertains to film, musicology and ethnology. He devised a grand organism of interconnection and made its presence known in virtually everything he did. Much of Smith’s work has and will continue to resonate all over the world.

[gadflyonline.com, January 29, 2002]

01/29/2002