You have no items in your cart.

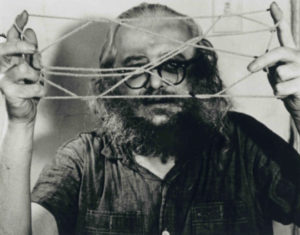

harry smith

1923-1991

Full Biography

Harry Smith: An Ethnographic Modernist in America

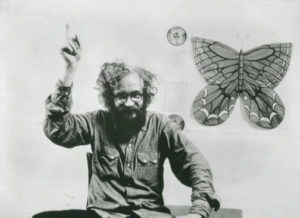

Harry Smith was an artist who delved into multiple disciplines in a quest to understand the structure and essence of what he considered universal patterns. He looked at the world through the eyes of an ethnographer and cultural anthropologist and had a voracious appetite for information. Eschewing standard ethnographic practices Smith explored both “high” and “low” art forms, mixing the local and the global and recombining these with a hallucinatory notion of “making it new.” For a select few in various disciplines Smith’s work has been recognized as dense, complicated and visionary. But in the years since his death, we have begun to develop a more holistic view of the connections between the various aspects of his artistic output.

Harry Smith was a musicologist, an experimental filmmaker and compiler of folklore; he was also adept as a painter, linguist, anthropologist, and magician. He collected books, records, artifacts, and sound recordings using them as the basis of his works of art, as well as the raw materials for his anthropological and musicological research. His Anthology of American Folk Music was credited as triggering the folk music revival of the 1960s and in the past decades has become the primary and defining document in the alt-country/singer-songwriter movement.

Harry Everett Smith was born on May 29, 1923 in Portland, Oregon. His childhood was spent in the Pacific Northwest, primarily Bellingham, and Anacortes, Washington. His parents were theosophists, exposing him to a wide range of pantheistic ideas. Despite his provocative statement to an interviewer that his father was Aleister Crowley, his father was in fact Robert Joseph Smith. Harry’s father worked in the salmon industry as a marine engineer, boat captain and, after the decline of the salmon industry, as a night watchman for the Pacific American Fisheries, which was one of the largest salmon canneries in the world. His mother, Mary Louise, was a teacher on the Lummi Indian reservation. Smith’s paternal ancestors had been prominent freemasons. Smith’s father gave him a fully equipped blacksmith shop for his twelfth birthday and told him he should turn lead into gold, the traditional aspiration of the alchemist.

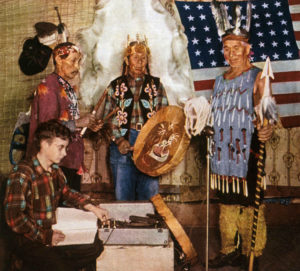

From an early age Smith was collecting and recording rituals, music and language and attempting to capture them and their ‘essence.’ By the age of 15 Smith had spent time on the Lummi and Salish Indian reservations recording songs and rituals, collecting sacred religious objects, and compiling a dictionary of several Puget Sound dialects. He was depicted in American Magazine posing with local Indian chiefs recording the spirit dance at the Lummi potlatch. “I took photographs, and made recordings, collected string figures—anything I’d seen in the standard anthropology books about what was liable to be the culture elements in the area.”

“When I was a child somebody came to school one day and said they’d been to an Indian dance and they saw someone swinging a skull on the end of a string; so I thought hmmmm, I have to see this. I sometimes spent three or four months with them during summer vacation or in the winter, while I was going to junior high or high school. In an effort to write down dances, I developed certain techniques of transcription. Then I got interested in the designs in relation to music. That’s where it started from. It was an attempt to write down the unknown Indian life. I took portable recording equipment all over the place before anyone else did and recorded whole long ceremonies sometimes lasting several days. Diagramming the pictures was so interesting that I then started to be interested in music in relation to existence.”

From an early age Smith took a nontraditional approach to ethnographic observations. He saw underlying patterns emerge from disparate cultural activities and he decided that his life’s work would be to uncover these patterns and find methods for their transcription. His stated ambition in the high school yearbook was to be a composer of symphonic music.

From an early age Smith took a nontraditional approach to ethnographic observations. He saw underlying patterns emerge from disparate cultural activities and he decided that his life’s work would be to uncover these patterns and find methods for their transcription. His stated ambition in the high school yearbook was to be a composer of symphonic music.

As a teenager Smith began collecting records which was to become a lifelong obsession. The first record he heard was a “Tommy McClellan record that had somehow got into this town by mistake. It sounded strange and I looked for others. I started looking in other towns and found Yank Rachell records in Mount Vernon, Washington. Then during the record drive—I arranged for other people to look for old records. People collected records because you could sell them for scrap.” During World War II, people brought out records from their basements and attics, to be melted down for shellac making them available for next to nothing.

Smith studied anthropology at the University of Washington for five semesters between 1942 – 44. Old transcripts reveal that he took courses including the Evolution of Man, American Indigenous linguistics, geology, and principles of race and language.

After Smith’s brief foray into a traditional academic environment, he visited the Bay Area where he attended a Woody Guthrie concert at Joe Beck’s Union Hall where he smoked marijuana for the first time. The Bay Area at that time had a thriving cultural scene that frequently embraced theosophical and spiritual approaches to art. Smith was instantly taken with this alternative lifestyle. It was Beat before Bohemians were called Beats, and embraced experimentation, drugs, sex, music, especially jazz, and alternative religions such as Buddhism and Taoism. Smith was fascinated by these cosmic combinations and promptly relocated to Berkeley.

His early interest in painting and film brought him into contact with other “color music” artists such as Oskar Fischinger, Jordan Belson, Hy Hirsh and Norman McLaren. These artists formed the core of West Coast experimental cinema movement, which was showcased in the Art in Cinema series, run by Frank Stauffacher & Richard Foster at the San Francisco Museum of Art in the mid 1940s. The Art in Cinema series was instrumental in programming new work plus current and historical avant-garde films from Europe, exposing them to west coast audiences. Smith’s films were part of their regular film programs, and were occasionally shown with live jazz accompaniment.

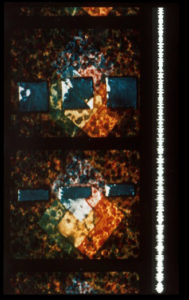

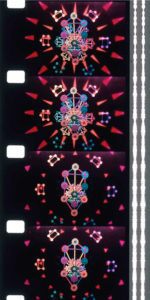

Smith’s first hand-painted films predate this period. He was surprised to find that others had done similar frame-by-frame processes, but few matched the complexity of composition, movement and integration of his own work. His methods required years of intricate labor, working alone, batiking and painting on 35mm frames or cutting out images to be meticulously filed and organized.

Although Smith’s early films were originally made without sound, he began to think about developing his work into experiments in visualizing music. The concept of blending sound, image and the senses, a process frequently enhanced by drug use, was anessential part of this process. The fusing of color with musical tones, and paintings with music, was for Smith a form of synesthesia. Synesthesia describes the overlapping of the senses, seeing colors when hearing sounds, tastes invoking colors, or images made to embody sounds.

Smith began to explore non-objective art thru the work and synaesthetic theories of painters Vassily Kandinsky, Rudolph Bauer and Franz Marc. He was interested in the correspondences between the senses from a mystical perspective. For him, this was an integral part of reconciling one’s existence within the universal. This core concept brought him into dialogue with his colleague Jordan Belson. Belson was a painter, filmmaker and commercial artist. They shared a number of interests including music, eastern mysticism, psychedelics, collage, and surrealism.

In San Francisco during the 1950s, Bebop was in its heyday and was becoming the defining expression of the generation. Smith found that its combination of complex structures and improvisation was uniquely suited to his cinematic investigations. Smith became a regular on the local scene, eventually moving to the hub of jazz culture, the Fillmore District where he rented a room over the prominent club, Jackson’s Nook. He was inspired by the environment: the live gigs in small clubs that turned into late night/early morning sessions, the drugs and the direct contact with the, and began a series of artistic experiments.

Smith recalled: “I had a really great illumination the first time I saw Dizzy Gillespie play. I had gone there very high, and I literally saw all kinds of colored flashes. It was at that point that I realized music could be put to my films.” At Jimbo’s Bop City, an infamous waffle house and late night jazz club, Smith would show his films to musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Thelonius Monk, as they improvised to the images on the screen. These early jazz films were experiments in visualizing music. They were created to be synchronized with particular jazz works. This synesthesiac fusing of color with sound and paintings with music, was for Smith a lifelong exploration. Pythagoras (whom Smith invokes at various points) understood that the “music of the spheres implied cosmic fusion, and he considered it the greatest philosophical and spiritual achievement because it ultimately reconciled the illusory world with the universal and abstract world.”

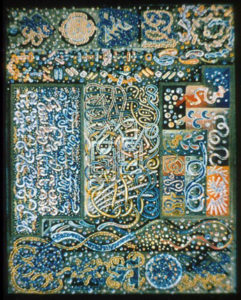

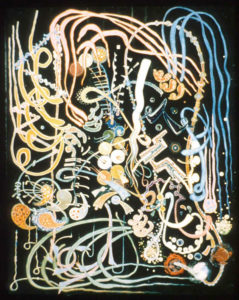

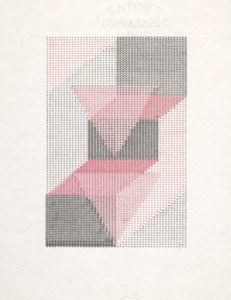

Smith also engaged with jazz in a series of paintings in which each paint stroke represents a musical note. He described these works as follows,“It is a painting of a tune by Dizzy Gillespie called Manteca. Each stroke in the painting represents a certain note in the recording. If I had the record I could project the painting as a slide and point to a certain thing. This is the main theme in there. Each note is on there. The most complex one is this one, one of Charlie Parker’s records. That’s a really complex painting. That took five years. Just like I gave up making films after that last hand-drawn one took a number of years, I gave up painting after that took a number of years. It was just too exhausting. There’s a dot for each note and the phrases that the notes consist of are colored in a certain way or made in a certain path.”

In San Francisco Smith continued his obsessive record-collecting, consulting with noted musicologist Bertrand Bronson (his landlord,) borrowing from other collectors (a popular line for pilfering from friends was that the records would be of better use in his collection) and regularly scouring local record stores in the surrounding area with his discerning eye.

Smith moved to New York City in 1951 with patronage from Hilla Rebay of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, now the Guggenheim Museum. He was referred to Moe Asch of Folkways Records, a small company started in 1948 that specialized in traditional and contemporary musics from around the world. Asch’s ambitious goal was to document the entire world of sound and to this day he still keeps everything in print. Harry offered to sell off some of his collection for much needed financial resources. Asch, impressed with Smith’s erudite knowledge challenged Smith to produce a collection of his own.

Smith moved to New York City in 1951 with patronage from Hilla Rebay of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, now the Guggenheim Museum. He was referred to Moe Asch of Folkways Records, a small company started in 1948 that specialized in traditional and contemporary musics from around the world. Asch’s ambitious goal was to document the entire world of sound and to this day he still keeps everything in print. Harry offered to sell off some of his collection for much needed financial resources. Asch, impressed with Smith’s erudite knowledge challenged Smith to produce a collection of his own.

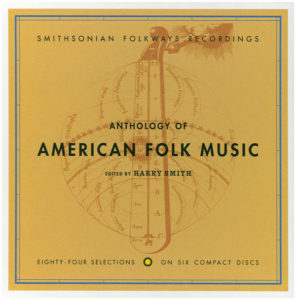

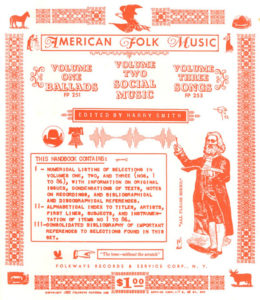

The Anthology of American Folk Music was the result. It was released on Folkways Records in 1952, in three volumes of long playing 33 1/3 microgroove technology and consisted of 84 commercially recorded 78’s, comprised of Appalachian folk songs, fiddle music, gospel, hillbilly, blues and Cajun tunes. At first glance one knew the Anthology was a unique art piece, a grand formula, weird and utterly different from other records available at the time. Although Smith didn’t purport to give a definitive version of American folk culture, he attempted to use the wisdom of the country’s marginalized populations to portray a distinctly American experience in all its oddity and complexity. Using American vernacular music as raw material, the Anthology presented a previously unexplored cultural history of America. The cover featured a Theodore DeBry engraving from a Robert Fludd 17th century compendium on mysticism, of what Smith called a “Celestial Monochord” being tuned by the hand of god.

Accompanying the records was a strange looking booklet, edited by Smith’s own hand. It was decorated with cut-outs from Sears Roebuck and farm catalogs, facsimiles from the 78 record covers, musical instruments from turn of the century catalogues and photographs of the performers, sheet music and collages using various ephemera. Using a heavy black type, Smith listed and numbered each song by title, instrumentation, discographic information (recording date, label and master number) and bibliographic information. Faux newspaper headlines created by Smith offered darkly humorous summaries of each song. For example, Smith’s entry for Mississippi Boweavill Blues read: “Boweavill survives physical attack after cleverly answering farmer’s questions.” A song about the Titanic states: “Manufactured proud dream destroyed at shipwreck. Segregated poor die first.” For King Kong Kitchie Kitchie Ki-Me-O: “Zoologic Miscegeny achieved in mouse frog nuptials, relatives approve.” The booklet was not only humorous, but a testament to Smith’s encyclopedic knowledge of relevant source material and song provenance. The inclusion of quotations from mystics Robert Fludd, Rudolph Steiner, Aleister Crowley and R.R. Marrett reflected his spiritual bent; Smith pointedly acknowledged them as having “been useful to the editor in preparing notes for this handbook.

Smith eschewed the standard musicological terms and broke the collection into three distinct volumes: Ballads, Social Music, and Songs, with a different color cover for each based on the elements; blue for air, red for fire and green for water and eventually on Volume Four, brown for earth. Using his own classification system, Smith intentionally never identified the race of the performers, as was the practice in the ethnomusicology field. Crossing racial and ethnic boundaries, he decontextualized the songs, and deliberately left the listener free of any bias, leaving people to wonder for years about the performers. Of dubious legality, since there were no licensing or artist fees paid, the Anthology was one of the first concept compilation record sets to be issued.

The collection was comprised of commercial recordings issued between the years “1927, the year electronic recording made possible accurate music reproduction, and 1932 the period between the realization by the major record companies of distinct regional markets and the Depression’s stifling of folk music sales. During this five-year period American music “still retained some of the regional qualities evident in the days before the phonograph, radio and talking pictures (that) had tended to integrate local types.” Smith refers to a brief period in the late 1920s when records were made for local audiences, and regional differences remained distinct. Professional musicians in small towns were still relatively isolated from outside sources and the influence of the mass market. In this short window of time, singers and musicians were recorded before they knew how they sounded on records, and while performing vernacular music learned through oral tradition. Technological advances brought rapid change to the recording industry; many performers altered their styles after they heard themselves in recorded form, or in response to new recording and broadcast technologies such as microphones, studio sound mixing and radio.

The collection was comprised of commercial recordings issued between the years “1927, the year electronic recording made possible accurate music reproduction, and 1932 the period between the realization by the major record companies of distinct regional markets and the Depression’s stifling of folk music sales. During this five-year period American music “still retained some of the regional qualities evident in the days before the phonograph, radio and talking pictures (that) had tended to integrate local types.” Smith refers to a brief period in the late 1920s when records were made for local audiences, and regional differences remained distinct. Professional musicians in small towns were still relatively isolated from outside sources and the influence of the mass market. In this short window of time, singers and musicians were recorded before they knew how they sounded on records, and while performing vernacular music learned through oral tradition. Technological advances brought rapid change to the recording industry; many performers altered their styles after they heard themselves in recorded form, or in response to new recording and broadcast technologies such as microphones, studio sound mixing and radio.

Smith stated “The Anthology was not an attempt to get all the best records, but a lot of these were selected because they were odd—an important version of the song, or one which came from a particular place. Instead they were selected to be ones that would be most popular among musicologists, or possible with people who would want to sing them and maybe improve the version. They were picked out from an epistemological, musicological selection of readings … I was looking for exotic records. Exotic in relation to what was considered to be the world culture of high class music.” “The whole Anthology was a collage. I thought of it as an art object,” Smith states. Taken as a whole the Anthology presented a narrative of “the old, weird America,” as Greil Marcus described it in his book Invisible Republic. It was an America of many voices, speaking of poverty, violence, oppression and unrequited love. Smith’s sequencing was a deliberate act that created an active dialogue between the individual tracks. The complex interweaving of themes and ideas generated multiple narratives – one of the most striking of which addressed racial categorization within the music industry. During the 1920s race records had been marketed to exclusively black audiences, and Smith felt that record companies made caricatures of the performers in the way they presented them. Smith refrained from identifying musicians in racial terms in his liner notes, and made his feelings on the subject clear with his observation that “the advertising on these envelopes gives a good idea of the companies attitude toward their artists.[sic]”1 Crossing racial and ethnic boundaries, he decontextualized the songs, and deliberately left the listener without a basis for bias.

The Anthology was released at the height of McCarthyism as national hysteria over Communism’s infiltration began to take effect. Folk music at the time was made up of divergent streams, from the soft easy-listening sounds of bands such as the Weavers and the Kingston Trio to the socially and politically motivated music of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie. Unlike the left-wing folk movement which defined protest songs as music of organization, many of the tunes Smith chose for social music are dance tunes or spirituals—a very different definition of the social. Confronted by a homogenized, bland picture of Americana during the Eisenhower era, people sought out a more authentic version of vernacular music, and for many the Anthology was a revelation. It exposed a whole new audience to a collections of songs, performers and cultures that were previously unknown or overlooked. Bohemians, beatniks and college kids from the Northeast started learning these songs, obsessively playing them until they had memorized every last one. “It was the Bible for hundreds of us” stated singer Dave Van Ronk.

Referred to as the “founding document of the American folk revival,” and a “one-man cultural revolution,” its songs continue to be performed by successive generations of singer/songwriters and remain a central component of the American vernacular songbook. The Anthology was re-released in 1997 on compact disc with expanded notes and essays and CD Rom capability and was part of the resurgence of the alt-country movement embodied by artists like Wilco, Beck and Lucinda Williams.

Smith’s involvement with music and recording continued into the sixties and seventies as he produce the first album by the Fugs, in 1965 and Allen Ginsberg’s First Blues as well as unreleased recordings of Gregory Corso’s poetry and Peter Orlovsky’s songs. Smith spent part of this era living with groups of Native Americans and recording the peyote songs of the Kiowa Indians.

Smith was also a pioneer of avant-garde and experimental film. Smith started making films in the mid 1940s and continued throughout his life. By 1957 Smith had finished his first eight films, a body of work that came to be known as Early Abstractions.

The first films were meticulously hand crafted and painted, then optically printed. Working frame by frame, Smith devised a range of techniques to apply layers of paint, stencils or cut out shapes to reveal movement across a two – dimensional plane. A series of short films numbered and strung together, the Early Abstractions ranged from geometric patterns in black, white and color, to complex collages revolving around a surrealistic barrage of disparate esoteric imagery culled from various texts. The range of techniques and styles in his forty years of output is astounding, each film builds on the previous, with the subject matter and techniques increasing in complexity.

Smith defined his work by stating: “My cinematic excreta is of four varieties:–batiked abstractions made directly on film between 1939 and 1946; optically printed non-objective studies composed around 1950; semi-realistic animated collages made as part of my alchemical labors of 1957 to 1962; and chronologically superimposed photographs of actualities formed since the latter year.

Smith defined his work by stating: “My cinematic excreta is of four varieties:–batiked abstractions made directly on film between 1939 and 1946; optically printed non-objective studies composed around 1950; semi-realistic animated collages made as part of my alchemical labors of 1957 to 1962; and chronologically superimposed photographs of actualities formed since the latter year.

All these works have been organized in specific patterns derived from the interlocking beats of the respiration, the heart and the EEG Alpha component and they should be observed together in order, or not at all, for they are valuable works, works that will live forever—they made me gray.”

Very little serious attention has been given to Smith’s work in the visual arts but this constitutes an important part of his oeuvre. Smith stated: “I was mainly a painter. The films are minor accessories to my paintings. My paintings were infinitely better then my films because much more time was spent on them.” Due to Smith’s irascible nature and his total disregard for the world of commerce with the exception of a highly subjective system of bartering, most of his paintings and design work have been lost, stolen and traded on the drug market.

Another area of Smith’s interests were museological and resulted in the creation of a number of collections. Smith was the world’s self-described leading authority on string figures, having mastered hundreds of forms from around the world. He studied many languages and dialects, including Kiowa sign language and Kwakiutl. Smith donated the largest known paper airplane collection to the Smithsonian Institute’s Air-Space Museum , they are now housed in the Getty Research Institute’s Special Collections. He was a collector of Seminole textiles, tarot cards and Ukrainian Easter Eggs and used to display them in his small room at the Chelsea Hotel. In his closet he stored huge beaded Indian women’s costumes. Smith said of his collections: “They are indexes to a great variety of thoughts. They’re like encyclopedias of designs. You can look in the Oxford English Dictionary if you want to study words, but being that the designs on the eggs are so ancient, they’re like 20 or 30 thousand years old, it’s like having something superior to a book. These collections have been built up fundamentally to have an index of design types that I might want to use in my paintings.”

He continues, “It has something to do with the desire to communicate in some way, the collection of objects. All are methods to communicate according to the cultural background that they have. So I’m interested in getting series of objects of different sorts. It does seem apparent, since I started collecting records, that there are definite correlations between artistic expressions in one particular social situation, like a consistency in small lines in Aboriginal Australian art. And music is the same thing, short words. It may be connected with language. My recent interest has been much more in linguistics then it has been in music, because it’s something that can be satisfactorily transcribed.”

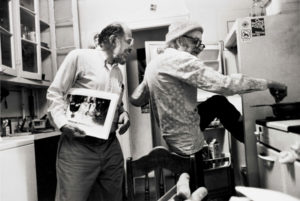

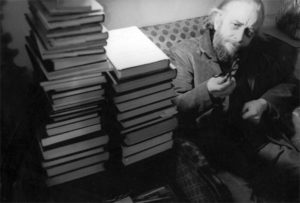

A student of the Kaballah and various esoterica, Smith was involved in the occult to varying degrees. During the final years of his life he was a resident of the Chelsea Hotel. A visit to Harry’s room there was always a bizarre escapade. He had books and records piled up on the floor, (he was a voracious book collector) and kept a collection of gourds and street signs from bums in one corner and weird experiments in the freezer. The room disoriented one’s senses, not just because of the copious amounts of marijuana, but also because Smith’s seemingly unlimited ability to jump from one disparate subject to the next left one’s brain swimming..

When you walked into his room you never knew what you’d find there, what mood he’d be in, what chaos was about to unfold, or what motley characters would be there, from various artists and poets, to a Harley Davidson biker to a matronly socialite, or a person he just met on the street. Robert Frank stated that Smith’s genius lay in the very fact that he recognized that the difference between a Bowery bum and an erudite scholar is negligible, he mingled freely with both. Smith’s ability to cull from high and low cultures defined his existence. He was completely dedicated to this lifestyle and the suffering that came with it. For him, destruction was as important as creation. The alchemist’s focus is on THE PROCESS, the preparation. For Smith, the focus was not the completed work, but the act of discovering, doing the reading, the research, the understanding of various systems of knowledge.

It’s important to note that Smith lived his life in relative poverty, borrowing, selling and trading his artwork, preferring to spend whatever money he had on books and supplies rather then food. Harry Smith had few regular jobs and his years in New York found him moving from hotel to SRO to a Bowery flophouse, but always ending back up at the Chelsea Hotel.

Harry spent his last years in Boulder, Colorado, (1988-1991) as “shaman in residence” at Naropa Institute where his life’s work culminated in a series of lectures. There he continued collecting and research. His last formal project was a series of audio recordings started in the East Village, New York City and continued in Boulder entitled “Materials for the Study of Religion and Culture of the Lower East Side” or “Movies for Blind People” This collection consists of cassette tape recordings made on a Sony Pro Walkman with sounds of Haitian Street Fairs; Hispanic celebrations; local churches; children’s jump rope rhymes; folk and rock music on the street and in local clubs; Bowery bums coughing and praying on their deathbeds; Gregory Corso; Allen Ginsberg; the noises of Tompkins Square Park; cows at sunset and more, recorded during the 1980s.

On top volume, listening on headphones, Smith seems like a symphonic composer of the highest magnitude. Harry Smith died in 1991 at the Chelsea Hotel.